economist.com

Worries about fraud and fragmentation may prompt a shake-out in the crowded online-ad industry

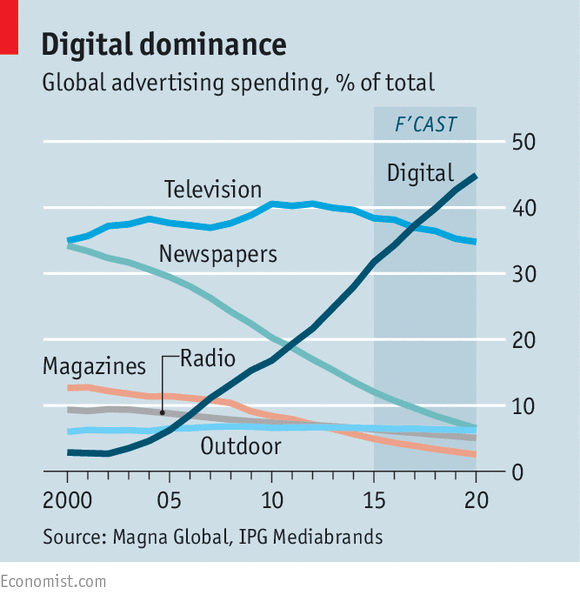

THIS year, for the first time, advertisers in America may spend more online than on television. Worldwide, online ads may surpass television in 2017, predicts the forecasting unit of Interpublic, a giant ad agency. Digital advertisers’ ambitions border on the divine. They are omnipresent, nestling their ads in news sites, search results and Instagram feeds. They are increasingly omniscient: no longer do advertisers know just general things about you—a worldly professional, say, with superb taste in journalism—but they target you, specifically. Omnipotence, however, is proving harder to achieve.

The industry has not so much a supply chain as a tangle. More than 2,500 companies are involved in the supply of digital ads, according to Luma Partners, an investment bank. Marketers worry that their ads will linger unseen in obscure slots or worse, be served to robots posing as human consumers. Meanwhile millions of real ones, fed up with online ads, want to block them. Among investors, enthusiasm for “ad tech” has waned. Digital advertising’s woes are not existential. Spending will continue to grow. But the current turmoil is likely to reshape the industry.

“Programmatic”, or automated, buying and selling of ad slots was supposed to make advertising online simpler, and in many ways it has. Advertisers bid for space on a webpage that a consumer has just clicked on, based on cookies and other tags that are tracking his online activities. The auction is held, and the “winning” ad transmitted, within milliseconds. The idea is to help publishers get the best price for their slots and advertisers the best return on their investment.

The trading of online ad slots is as complex as it is fiendishly fast. Thousands of firms jostle to analyse consumer data and buy, sell and monitor ads. Middlemen repackage “inventory” (as ad slots are known in the business), then sell it to other middlemen. An ad impression sold programmatically can change hands 15 times before finally being bought by an advertiser, notes Peter Stabler, an analyst at Wells Fargo, a bank. “We have an immature supply chain that is constantly evolving,” says Randall Rothenberg of the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB), which represents media and ad-tech firms. That brings both innovation, he argues, and headaches.

Some problems are more easily fixed than others. In recent years the various participants in the industry have bickered over “viewability”: webpages are usually bigger than the screens they are viewed on, so if a reader sees only part of an ad on his screen, for a fraction of a second, how much should the advertiser pay? The Media Rating Council (MRC), which sets the rules for audience measurement, now considers a display ad “viewable” if a consumer can see half of it for at least one second. Videos must be seen for two seconds.

But some advertisers want more. GroupM, a buyer of ad slots on behalf of consumer brands, considers an ad viewable only if the consumer can see all of it. Consumers must play at least half a video with the sound on. The MRC is still working on standards for ads on mobile phones.

On the whole, however, the debate over viewability points to online advertising’s promise, not its failings. It is impossible to know if a television viewer has gone to the bathroom during the commercials or if a Vogue reader skips a particular page of ads. Online, marketers have at least some means of tracking who saw what, the better to understand which ads work.

Fraud is a peskier problem. Bad actors hide within advertising’s supply chain, unleashing robots to “see” ads and suck money from advertisers. The subtly titled Trustworthy Accountability Group, backed by the industry’s trade associations, wants to create a registry of vetted online-ad firms and use special identifiers to track which firms get paid for each impression, the better to trace problems as they arise. AppNexus, which runs a big ad exchange, filters out ad slots that seem to be attracting lots of fake “readers”, offers rebates to advertisers which detect bot fraud and has cut the number of ad impressions sold by middlemen. Such steps will lower fraud, not banish it. The Association of National Advertisers reckons fake impressions will cost its members more than $7 billion this year.

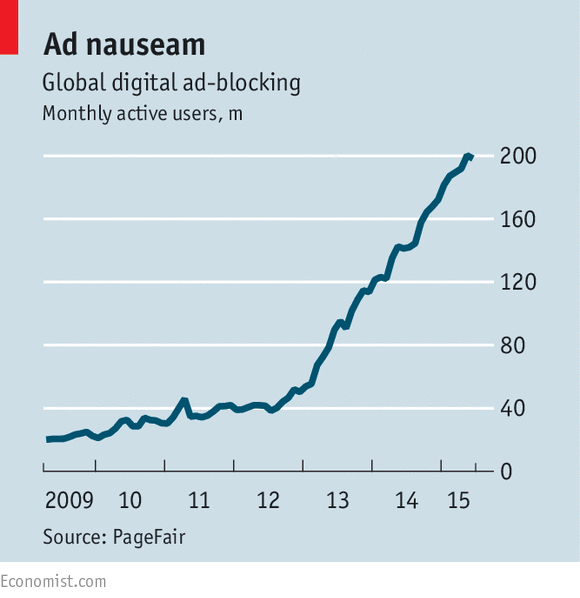

An even thornier challenge is the growing number of consumers blocking ads altogether (see chart). Some consider it creepy to be watched so closely. Third-party tags can be messengers for malware. Ads drain smartphones’ batteries and their users’ data plans. Tags to track viewability and bots make such things worse.

Little wonder, then, that AdBlock Plus, a popular tool, has been downloaded more than 500m times. The company keeps a list of ads it deems tolerable, and thus lets through. Sites with lots of ads, such as Google, pay a fee to be on the list. AdBlock Plus says this is proper, as the paying firms must still offer palatable ads. Critics, including the IAB, call it extortion.

Ad-blockers are most troubling for publishers, which rely on advertising revenue. But brands have reason to fret, too, if they cannot reach consumers online. The IAB is urging them to make advertisements less irksome, so that consumers are less inclined to block them. The Washington Post is one of many companies hoping that “native” ads, which mimic the paper’s editorial style, will be less annoying. But the company is also speeding page-load times and testing various dummy ads to see which types consumers dislike least. As these experiments continue, ad-blocking will impose broad costs on publishers, estimated by Wells Fargo at $4.6 billion in America and $12.5 billion globally this year.

A secular shift

All these problems may just be inevitable teething troubles. “We haven’t had this kind of transformation since television came in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s,” says Marc Pritchard, the marketing boss at Procter & Gamble, the world’s largest advertiser. Grappling with these challenges, however, may spur a shift in the industry’s structure. There will always be startups, particularly because technology changes so quickly. But on the whole, power is likely to move to fewer, larger companies.

Rob Norman, GroupM’s chief digital officer, expects advertisers to continue shifting towards large platforms such as Google and Facebook, and a select group of firms that agree to stricter standards on viewability. Brands’ concern about fraud and fragmentation may help simplify the supply chain. Some brand owners, such as Procter & Gamble, control their own programmatic buying.

Others are pruning the number of other firms they deal with. “We would always prefer fewer partners,” says Jamie Moldafsky, chief marketing officer for Wells Fargo. A variety of larger companies such as Yahoo, Oracle and Salesforce have bought up smaller firms, the better to offer themselves as one-stop shops to advertisers.

The best positioned firms, however, are Google and Facebook. Terence Kawaja, Luma’s founder, notes that the two companies have more than half of the mobile-advertising market, a share he expects to rise. Thanks to logins, each can track consumers from their computers to their phones and back again. Each has a broad, ever-expanding suite of services. On March 15th Google unveiled new tools, including one to manage data on customers.

Rivals are worried. TubeMogul, a provider of ad-buying software, has a new advertising campaign claiming that Google has excessive power. This is in part to defend its own interests—TubeMogul’s criticisms include Google’s decision to limit the ways by which brands can buy ad space on its YouTube video service. But it is not unreasonable to worry that the pressures to rationalise the fragmented online-ad industry might eventually push it too far in the other direction.

No comments:

Post a Comment